Working with Git repositories

Objectives

At the end of this self-learning lab, you should be able to:

- understand what is a VCS

- understand the Git workflow

- Initialize a git repo

- save changes of a repo in a commit

- navigate between commits

Motivation

What is a VCS? What is Git?

- Git is a VCS (Version Control System).

- It saves history of changes over time.

- You can try changing some code without worrying about being unable to rollback.

- Helps answering questions like:

- What changes did xxx make to the code?

- Who added this line of code?

- When did we add this code?

- Why did we add this code?

- Git is a DVCS (Distributed VCS).

- Multiple developers can work offline independently and merge their work together later on.

- No more sending "xxxx_v1.py" "xxxx_v2.py" "xxxx_v3.py" around... Wait, did we have two different "xxxx_v2.py"s from two different people?

What is a repository?

- A repository is a project in Git. Files related to the same project are stored in the same repository.

- Git stores the history of a repository using snapshots called "commits".

- Any copy of the repository contains the whole codebase and its history.

Basic Git workflow

+-----------+ +---------+ +------+ push +--------+

| Working | staging | Staging | commit | |-------->| |

| directory |---------->| area |--------->| HEAD | | GitHub |

+-----------+ +---------+ | |<--------| |

+------+ pull +--------+

There are three levels of file storage in Git:

- Working directory, where other programs will see your files

- Staging area, which is the version that Git will commit

- HEAD, which is the "clean" (unmodified) version of this repository that Git expects

Initializing the repository

There are two ways to create a repository:

- Create a brand new repository:

- Run

git initin the directory that you want to turn into a Git repository. You can also do this in a directory with existing files. - Clone an existing repository:

- We will talk about synchronizing your changes with other people in the next section.

When a directory is turned into (the root directory of) a Git repository,

it contains a .git subdirectory.

You can check this by running the ls -A command.

Tip

In Linux, a filename starting with a . is conventionally treated as "hidden" files

and are not displayed in user interfaces like ls and Ubuntu File Manager by default.

Try it yourself

Create a new folder named project under the home directory:

$ cd ~

$ mkdir project

$ cd project

Now initialize project as a Git repository:

$ ls -A

You will see a single line of output .git/.

Staging files

- Files in the working directory have to be "staged" to get tracked by Git.

- Use the

git add <file>command to stage files.

Try it yourself

First run git status to see that the working directory is clean

(i.e. working directory = staging area = HEAD):

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

Create a new file abc.txt inside project

and put the line some text in the file:

$ echo some text > abc.txt

You can also use other tools like

geditornanoto create a file

Now you can run git status again to see that abc.txt is an untracked file:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

abc.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

As the last line suggests, run git add abc.txt and try again:

$ git add abc.txt

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: abc.txt

Now abc.txt is staged but not yet committed

(working directory = staging area ≠ HEAD).

Let's try modifying the contents of abc.txt to something else:

$ echo some other text > abc.txt

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: abc.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: abc.txt

- the working directory has

abc.txtcontainingsome other text - the staging area has

abc.txtcontainingsome text - the HEAD has no

abc.txt

You can run git diff to see the difference between working directory and staging area,

and git diff --staged to see the difference between staging area and HEAD.

Run git add abc.txt again to stage the new version.

Tip

You can also run git add -A,

which stages all files under the repository.

.gitignore

Very often, we just git add -A or git add . to add all files quickly.

To prevent staging some files that we will never want to commit,

e.g. temp files, generated files, log files or personal files,

we list those files in a .gitignore file.

Try it yourself

First let's initialize a repo with this structure:

.

├── a.txt

├── b.log

├── foo

│ ├── bar

│ │ ├── b.log

│ │ └── d.log

│ └── c.log

└── qux

└── e.log

3 directories, 6 files

Try using touch and mkdir yourself to make this!

Let's run git add -A --dry-run to see what files Git will want to track with git add -A:

$ git add -A --dry-run

add 'a.txt'

add 'b.log'

add 'foo/bar/b.log'

add 'foo/bar/d.log'

add 'foo/c.log'

add 'qux/e.log'

As expected, Git will try to track all files.

Let's try excluding all files ending with .log:

$ echo "*.log" > .gitignore

$ git add -A --dry-run

add '.gitignore'

add 'a.txt'

Caution

Remember the "" around arguments where you really want a *,

otherwise the shell will expand the argument

into a list of filenames matching that pattern.

You can see that all .log files are excluded.

If we just wanted to exclude *.log files directly under repository root

(but not those in subdirectories),

we add a / in front of the line:

$ echo "/*.log" > .gitignore

$ git add -A --dry-run

add '.gitignore'

add 'a.txt'

add 'foo/bar/b.log'

add 'foo/bar/d.log'

add 'foo/c.log'

add 'qux/e.log'

What if we just want to exclude .log files under foo?

$ echo "/foo/*.log" > .gitignore

$ git add -A --dry-run

add '.gitignore'

add 'a.txt'

add 'b.log'

add 'foo/bar/b.log'

add 'foo/bar/d.log'

add 'qux/e.log'

Oops, foo/bar/b.log and foo/bar/d.log are still included,

because * matches any characters in filenames but not the /.

This will only exclude *.log files directly under /foo.

To allow any path components in the wildcard, we need **/*:

$ echo "/foo/**/*.log" > .gitignore

$ git add -A --dry-run

add '.gitignore'

add 'a.txt'

add 'b.log'

add 'qux/e.log'

We can explicitly exclude particular files using the ! prefix:

$ echo "*.log" > .gitignore

$ echo "!/foo/*.log" >> .gitignore

add '.gitignore'

add 'a.txt'

add 'foo/c.log'

Note that exclusion rules only work on files directly, but not on directories.

The following will NOT un-exclude /data/ros.log:

/data/

!/data/ros.log

.gitignore is staged in Git as well

(other people will still need to ignore the new files generated on their side!).

If you want to have personal gitignores that should not be staged,

you can also use the .git/info/exclude file.

This file is resolved as the same scope as the .gitignore at the repository root.

Committing changes

Recall that a commit is a snapshot of the repository. Committing changes is to create a snapshot of the current staging area.

Technically speaking, a commit contains the following data:

- Its parent commit(s)

- none if it is the initial commit

- multiple if it is a "merge" commit, which will be explained later

- The commit message, describing the changes in this commit

- Well-written commit messages are crucial for software maintenance.

- The commit author

- Git will use the name you set in the

git configcommand in the previous section.

- Git will use the name you set in the

- Changes since the parent commits

- Git does not really store a copy of all files, but just the difference between commits.

To create a commit, use the command git commit -m "<your message here>".

Try it yourself

Let's commit our abc.txt to the HEAD! Simply run the command:

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

[master (root-commit) 23591cd] Initial commit

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 abc.txt

The code 23591cd is called the "commit sha".

Now git status thinks the directory is clean,

because the latest HEAD contains the abc.txt file.

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

How often should I commit?

There are many different paradigms of sizing git commits. Some prefer a minimalist approach, where each commit is the minimal set of changes related to the same thing. Some prefer not to commit until the whole project is fully working.

Either way, in general, here are some rules of thumb:

- Do not mix unrelated changes in the same commit.

- If we revert a certain commit in the future, we will revert the unrelated changes altogether. This will make things very confusing.

- Test your code before committing.

- Depending whether you are committing to the "production branch", there are varying barriers to committing.

- Regardless, nobody likes seeing a commit history where you first commit a file full of syntax errors followed by dozens of commits, one for each syntax error.

- Commits should be semantic.

- If you are using the GitHub web editor, you would create one commit each time you edit a file. This kind of committing pattern is often frowned upon.

In M2, we may develop code locally, then upload them to robots via Git commits to test on robots. Although this is not a very good pattern, this is usually acceptable as long as you don't create many many commits every time you want to print a debug message or change something very minor that does not even constitute as a "fix".

However, it is perfectly fine to create a commit that fixes a typo; in fact, typo fixes should have their own commits.

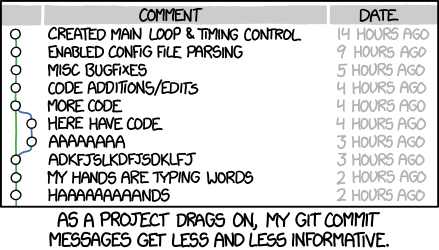

Writing clear and concise commit messages

Commit messages must explain the purpose of every commit, no matter how minor it is.

It is important for navigating code history and knowing why some code was added,

so that you don't get $ git blamed wrongly all the time.

In M2, we follow the following format for commit messages in regular ROS package repos:

<type>: Short, one-line summary

Detailed explanation goes on here

(This restriction does not apply to nontrivial commits from Git like merges and reverts)

The <type> is typically one of the following:

<type> |

Description |

|---|---|

<feat> |

New features |

<fix> |

Bug fixes |

<refactor> |

Refactor, e.g. changes that rename some existing functions |

<style> |

Reformatting, no semantic changes |

<docs> |

Documentation changes |

<test> |

Adding tests |

<chore> |

Other non-code changes |

Viewing Git history

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

git log |

Commit history of the whole repository |

git log <file> |

Filter of git log for commits changing a particular file/directory |

Try it yourself

$ git log

commit 23591cd5e33cfba9706df72b71e441c72a2b7407 (HEAD -> master)

Author: SOFe <[email protected]>

Date: Sun Aug 30 17:38:09 2020 +0800

Initial commit

The full length of a git sha is 40 characters long (as seen in git log),

but usually we just use the first 7 characters.

Most commands accept using both the 7-character version and 40-character version

to identify a commit.

Deleting a git repository

When you delete a local git repository with rm -r, you get a message like this:

$ rm -r my-repo

rm: remove write-protected regular file 'my-repo/.git/objects/78/981922613b2afb6025042ff6bd878ac1994e85'?

This is because git marks all internal objects as read-only

to prevent accidental user modification (by chmod u-w).

We can force delete the whole directory using rm -rf:

$ rm -rf my-repo